THE PAIN OF BEING AN ARTIST

‘Artists give us a place to go where we can access beauty and truth, that is their great contribution, but they pay a price for doing that for us. It is their great gift to us.’

Jeremy Griffith

Following is Jeremy Griffith’s essay about the power of art in Freedom Essay 44 - Art makes the invisible visible:

As I have explained in my book FREEDOM, from an all-loving, all-sensitive and completely happy original innocent instinctive life, we humans then—for a reason we have had absolutely no real understanding of until now—turned into ferociously selfish, competitive and aggressive monsters. No wonder then that virtually everyone when they were adolescents resigned themselves to shamefully hiding in what the great philosopher Plato described as a metaphorical cave of darkness away from any light that would reveal the truth of their horrifically corrupted condition and the truth of our species’ once cooperative, selfless and loving innocent state. Until we could understand our corrupted human condition, denial of it, and of the truth of our species’ innocent past, was absolutely necessary to protect ourselves from unbearable self-confrontation.

So denial has been extremely precious for the human race, but having to live in complete darkness, complete denial, meant living in a world that was so devoid of truth and meaning and beauty that that could also be unbearable. Clearly, some truth and beauty was needed to counter all the denial/darkness/black-out the human race was living in—and that is precisely what great art has provided. It allowed the light of some honesty about our corrupted human condition and some access to our species’ lost state of all-sensitive and all-loving innocence to escape from the dark cave in which we have been hiding. The literature Nobel Laureate Albert Camus recognised how art provides a counter to all the darkness and confusion of the world when he wrote, ‘If the world were clear, art would not exist’ (The Myth of Sisyphus, 1942).

Great artists, be they painters, sculptors, singers, musicians, actors, dancers, poets, writers, architects or designers, are basically people who either didn’t properly or fully resign to living in denial of the truth of our immensely corrupted human condition and to blocking out all the exposing and confronting sensitivities that our original innocent instinctive self or soul has access to; and/or, people who cultivated access back to the truth of our corrupted human condition and to the sensitivities of our original instinctive self after they became resigned to living in denial of the human condition. Occasionally a person’s protective block-out develops, as it were, a crack or tear in it, either because they didn’t fully adopt denial or block-out when they were adolescents, or because they cultivated that crack or tear in their resigned state of block-out. Through this small rent these people can touch upon and reveal the truth about the human condition—whether it is the true horror of our corruption, or some of the true beauty that exists on Earth—but often, as will be explained, at great cost to themselves.

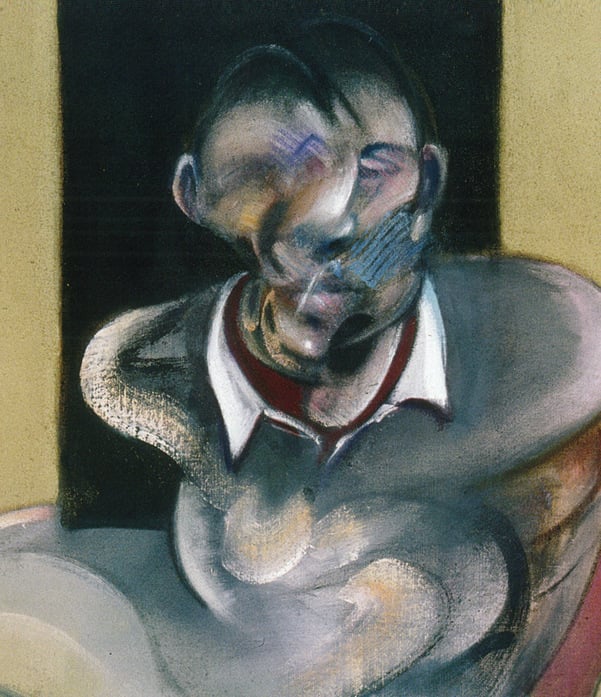

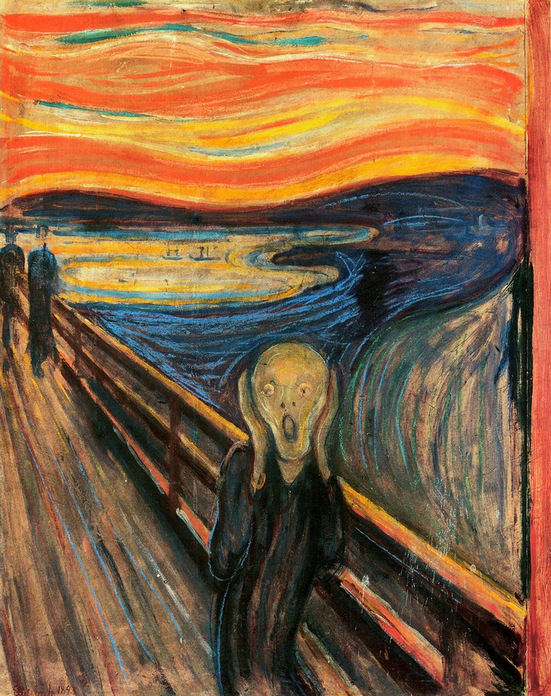

One benefit of arts like painting and music over the written or spoken arts was that truth about our corrupted condition and lost sensitivities that are denied or blocked-out when we resigned could be more openly acknowledged because such truths weren’t being presented in too direct and thus too confronting a way. More truth has been able to be revealed through artistic mediums that weren’t too explicit. In the case of music, the great novelist Victor Hugo made this point when he wrote, ‘Music expresses that which cannot be said and on which it is impossible to remain silent’ (William Shakespeare, 1864). In the case of painting, we find that from Francis Bacon’s tortured self-portraits and Edvard Munch’s terrifying, human-condition-revealing The Scream, to the true-beauty-in-the-world-revealing paintings of Van Gogh and Gauguin, this artform has allowed the agony and the ecstasy of the human condition to be expressed in a way that the written or spoken word would not be able to reveal without being too confrontingly direct and explicit. In arts like painting and music, everyone is free to recognise the truth that’s being revealed to the extent that they can cope with that truth.

-

Bacon’s Study for self-portrait, 1976

-

Munch’s The Scream 1893

Firstly, to look at Bacon’s Study for self-portrait and Munch’s The Scream (above). While in our day-to-day lives we block out the reality of the human condition, these paintings do expose the true nature of humans’ corrupted and alienated existence. Indeed, they depict what the Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing explicitly described when he wrote: ‘Our alienation goes to the roots…the ordinary person is a shrivelled, desiccated fragment of what a person can be…between us and It [our true selves or soul] there is a veil which is more like fifty feet of solid concrete’ (The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, 1967). But, it’s up to the individual viewer as to how much they’re able to acknowledge that what these pictures portray is the human condition—as I describe in FREEDOM:

“While people in their state of denial of what the human condition actually is typically find his [Bacon’s] work ‘enigmatic’ and ‘obscene’ (The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 Apr. 1992), there is really no mistaking the agony of the human condition in Bacon’s death-mask-like, twisted, smudged, distorted, trodden-on—alienated—faces, and tortured, contorted, stomach-knotted, arms-pinned, psychologically strangled and imprisoned bodies; consider, for instance, his Study for self-portrait (above left). It is some recognition of the incredible integrity/honesty of Bacon’s work that in 2013 one of his triptychs sold for $US142.4 million, becoming (at the time) ‘the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction, breaking the previous record, set in May 2012, when a version of Edvard Munch’s The Scream [another exceptionally honest, human-condition-revealing painting shown above on the right] sold for $119.9 million’ (TIME, 25 Nov. 2013).” (See paragraphs 124 – 125 of FREEDOM — you can also read more about Bacon’s work in various Freedom Essays including 31, 42 & 55.)

At the opposite end of the spectrum are artists who have the astonishing ability to break the hold of our tortured existence where we are preoccupied with denying and escaping the horror of our corrupted condition, and repressing the confronting and exposing sensitivities of our soul, and reveal some of the true beauty of our world that our soul has access to—artists who offer some glimpse of the magic we will be able to fully and properly access when we are no longer trapped behind the ‘fifty feet of solid concrete’ the human condition has wedged ‘between us and It [our all-sensitive soul]’. These paintings below by Van Gogh and Gauguin are good examples of great paintings that reveal the true beauty of our world.

-

Van Gogh’s The Sower, 1888

-

Gauguin’s Will You Marry Me?, 1892

I also explain this aspect of art in FREEDOM:

“Great art ‘can make the invisible visible’; it can cut a window into our alienated, effectively dead state and bring back into view some of the beauty that our soul has access to. After years of developing his skills, Vincent van Gogh was able to bring out so much beauty that resigned humans looking at his paintings find themselves seeing light and colour as it really exists for possibly the first time in their life: ‘And after Van Gogh? Artists changed their ways of seeing…not for the myths, or the high prices, but for the way he opened their eyes’ (Bulletin mag. 30 Nov. 1993).” (See paragraph 829 of FREEDOM.)

So while Bacon and Munch attract record-breaking prices because their honesty has immense cathartic power, it is through the art of masters such as Van Gogh and Gauguin that we are shown the radiant life that exists outside the human condition—and awaits humanity now that the human condition has been solved! (See Freedom Essay 15 on the transformation that is now possible for everyone.)

The often-referred-to ‘pain’—‘the torture’—of being an artist was that while most humans coped with life’s deeper questions by evading them, artists continually raised them. Through that crack or tear in their protective block-out, great artists could reveal the truth of our species’ corrupted condition and of the true beauty in our world that our corrupted, alienated, denial-practising condition blocks access to. BUT without the redeeming understanding of our corrupted, soul-repressed condition, what they were doing could be extremely confronting and hurtful for them.

It can be understood then why artists who were too honest for their degree of soundness, artists who confronted the dark extent of the human condition and the sensitivities of our soul when it was more than they were capable of enduring, could take themselves to the brink of madness and/or suicidal depression. For example, of the four artists featured above, Van Gogh went over this brink and did suicide; Gauguin attempted suicide; Munch wrote that at one period of his life, ‘My condition was verging on madness—it was touch and go’ (Edvard Munch: Paintings, Sketches, and Studies, ed. Arne Eggum, 1984, p.236 of 305); and Bacon led a tragically dissolute life, addicted to alcohol, sex and gambling. Truly, while great artists let some relieving truth out, they could pay a huge personal price of having to live a torturous existence.

The ominous Wheatfield with crows (1890), believed to be Van Gogh’s last work before he took his own life, conveys something of the terror of the human condition.

The very great South African philosopher, Sir Laurens van der Post, described the situation that faced writers and artists like Van Gogh in the following remarkably insightful quote: ‘The history of art and literature indeed contains as many examples of persons who have succumbed before the perils encountered in the world within as those who have been overcome by their difficulties in the world without. The asylums of the world are full of people who have been overwhelmed by what has welled up within them: instincts and intuitions shaped over aeons in which they had played no part, and imposed on them by life without their leave or knowledge. The person who enlists in the service of the imagination, as do the artist and writer, has continually to come to terms and make fresh peace with this inner aspect of reality before he can express his full self in the world without. Many are so appalled by the difficulties and terrifying implications of what they see within themselves that, after a few bursts of lyrical fire, they either retreat into the previously prepared positions conventionally provided for these occasions by their social establishments: or else they close up altogether or take to drink or commit suicide. Nor is there any comfort to be found in thinking that this kind of defeat is suffered only by the lesser breeds among artists and writers: there are too many distinguished casualties. There is, for instance, the uncomfortable example of Rimbaud who, though a poet of genius, found the implications of genius more than he could bear and took on the perils of gun-running in one of the most dangerous parts of Africa as a more attractive alternative. Yet before he turned a deaf ear to the profound voice of his natural calling, he had shaped a vision of reality which increased the range of poetry for good. One may regret his desertion, but surely no one who cares for poetry can read “Bateau Ivre” and “Les Illuminations”, for example, without some understanding of the power of the temptation, and an inkling of how exposed and vulnerable the ordered personality is to the forces of this world that the artist carries within him. The suicide of Van Gogh is another instance. We owe it to him that our senses are aware of the physical world in a way not previously possible (except perhaps by the long-forgotten child in all of us when the urgent vision is not yet tamed and imprisoned in the clichés of the adult world). But because of Van Gogh, cypresses, almond blossom, corn-fields, sunflowers, bridges, wicker chairs and even trains are seen through eyes made young and timeless again and our senses are recharged with the aboriginal wonder of things. Here was not only genius but also high courage. Yet nothing so well gives one the measure of these inner forces as the fact that they were able to destroy both courage and genius’ (from Sir Laurens van der Post’s Introduction to the 1965 edn of Turbott Wolfe by William Plomer, first pub. 1925, pp.34-36 of 215).

So while beauty could be the greatest inspiration, blindingly so at times, it could also be condemning and hurtful to humans because it confronted them with their apparent lack of beauty or perfection. The truth is, mere glimpses of beauty were all corrupted humans could cope with. The very great English poet William Wordsworth was making this point when he wrote, ‘To me the meanest flower that blows can give thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears’, for it is true that even the plainest flower can remind us of the unbearably depressing issue of our seemingly horrifically imperfect, ‘fallen’, apparently worthless condition.

Yes, great artists provided some truth to counter all the denial/darkness/black-out—they allowed the light of some honesty about our corrupted human condition and the true beauty of our world to escape from that dark ‘tomb’ in which we have been hiding, but without the defence for our corrupted condition, it could come at great personal cost to the artist. Thank goodness we now have the explanation of the human condition that at last frees humanity from the soul-destroying torture of the human condition, and transforms all our lives into a state of unimaginable happiness, beauty and excitement!

(You can read more of Jeremy’s insights into how humans have used painting and music and other artistic expressions to depict both our alienated state, and the world’s true beauty, in Video/Freedom Essay 10, which includes an analysis of William Blake’s great poem The Tiger; Freedom Essay 31 on Wordsworth’s great, all-revealing poem Intimations of Immortality; Freedom Essay 42 on cave paintings; Freedom Essay 43 on the power of ceremonial masks; and Freedom Essay 45 on prophetic songs. And for more elaboration on the development of art and culture, see chapter 8:11C of FREEDOM.)

World Transformation Movement North East England

World Transformation Movement North East England